Larissa Miller’s (LM) interview to Ruth O'Callaghan (ROC)

(In connection with publishing "Guests of Eternity".

transl. by Richard McKane, ARC Publ., 2008)

Interview published by Cinnamon Press, Envoi Issue 153, June 2009

About Larissa Miller in short:

Larissa Miller is a major Russian lyrical poet and author of many essays and articles in periodicals, and of fifteen books, one in English translation (Dim and Distant Days, Glas, 2000) and one bilingual English-Russian book of poetry (Guests of Eternity, ARC Publications, 2008). A member of the Union of Russian Writers since 1979, and of the Russian Pen Centre since 1992, she was short-listed in 1999 for the State Prize of the Russian Federation, having been nominated for the prize by the famous literary almanac Novy Mir. Many poems by Larissa Miller have been set to music and in 2003, 49 of Larissa Miller's poems were put together as a theatrical 'Poetical Performance' which played at various Moscow theatres.

Born in 1940 Larissa Miller graduated from the Foreign Languages Institute in Moscow and for many years works as a teacher of English, also since 1980 she has been teaching a women’s musical gymnastics system named after its creator, the renowned Russian dancer Ludmila Alexeyeva.

(See in more detail: http://www.larisamiller.ru.)

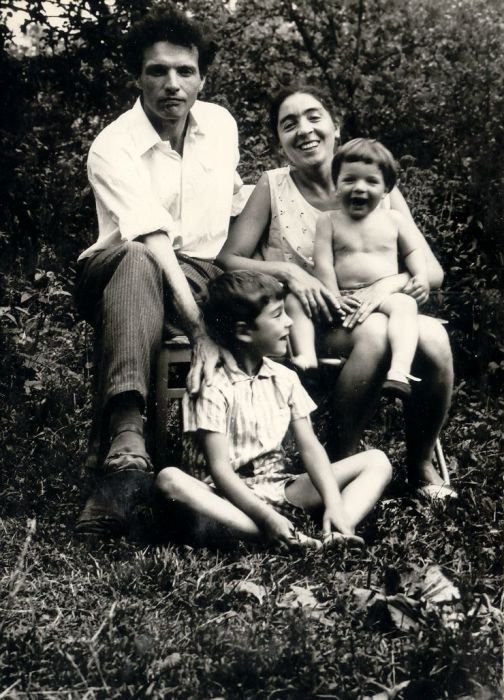

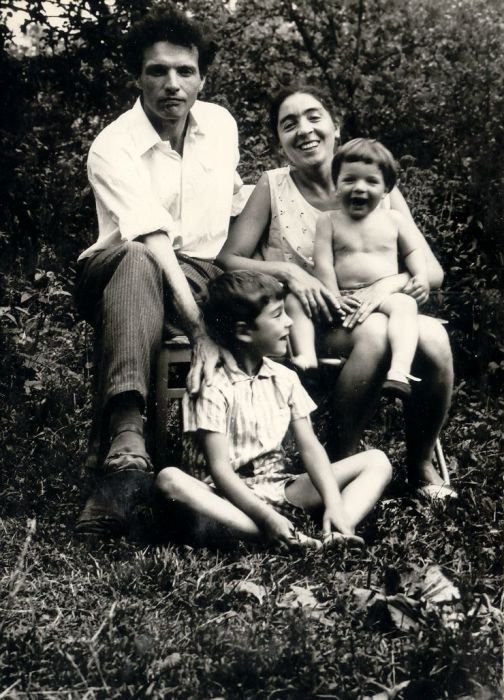

Larissa Miller with her husband and sons, Moscow, 1976.

ROC:

You grew up in post-war Moscow. Could you describe your childhood and adolescence in what must have been a very austere era.

LM:

My main sensation from those times is an acute sense of happiness. At least I can say that about my childhood, the first ten years of my life. My father was killed in the war in 1942 when I was only two and in 1951 my mother married again. My life changed radically, it was the end of my childhood. Perhaps adolescents all have problems with their own inner world and their environment. But in my early childhood, despite the privations of what you call “austere era” there was this sensation of happiness. I write about it in detail in my book Dim and Distant Days (trans. by Kathleen Cook and Natalie Roy, Glas, 2000). The book is available by order from all good bookshops.

ROC:

In Guests of Eternity your poems span four decades. However, I would like to take you back beyond that to ask if you could give a brief outline of the state of Russian poetry prior to the 1917 revolution?

LM:

In the early 20th century Russia, before the 1917 Revolution, the literary life was very vigorous and varied. The period came to be known as the Silver Age (as compared to the 19th century Golden Age of great Russian literature.) That was the time of such brilliant poets as Alexander Blok, Nikolai Gumilev, Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetayeva, Osip Mandelstam, to name just a few. Many poets began writing in the unique atmosphere of those years and reached their peak much later. Suffice it to recall my favourite poets Georgi Ivanov and Vladislav Khodasevich, who wrote their best poems already in their forced emigration, that is, after 1917. And whereas Alexander Blok practically fell silent after 1917 and Nikolai Gumilev was shot by the Bolsheviks, a huge body of works by such giants as Tsvetayeva, Mandelstam and Akhmatova belong to the post-revolution period.

ROC:

With the revolution came an upsurge of poets who were sympathetic to its initial ideals – the dignity of the proletariat. Hence in the 1920’s poets experienced a great deal of freedom. How did this contrast with the later Stalinist regime?

LM:

Without a doubt, the revolution opened up new opportunities for the people from the so-called lower classes. There was an atmosphere of great euphoria then. But if you look at the major figures, those who make the face of Russian poetry to this day you should name Vladimir Mayakovsky and Sergei Yesenin (both made successful debuts before 1917 and both committed suicide: Yesenin in 1924, and Mayakovsky in 1930), and also Nikolai Klyuev, Sergei Klychkov, Pavel Vassilyev, Eduard Bagritsky, and of course Boris Pasternak.

Mandestam, Klychkov, and Vassilyev perished in the Stalinist purges, as did many others. Pasternak and Akhmatova were spared miraculously. Tsvetaeva hanged herself in 1941. A terrible martyrology.

As for the freedom of the 1920s, it was not so simple either. There was no freedom, those were objectively very frightening years in Russia. Suffice it to read Solzhenitsin’s GULAG Archipelago. We can recall how the seriously ill Alexander Blok was not allowed to go abroad for treatment and so in 1921 he died. As for the public euphoria, yes it was there. In fact, everything is relative: the 1930s and 40s under Stalin were even more terrible than the 1920s but the public euphoria, pride for one’s socialist land were proportionally even greater. Such are the paradoxes of human psychology.

ROC:

In the ’60’s under Khruschev it is popularly thought that there was a thaw, a lessening of censorship – was this your experience?

LM:

The thaw was in the 1950s, after Stalin’s death in 1953. In the 1960, Khruschev already started “to tighten the screws”, and this process continued after his dismissal in 1964. That was the time I started writing poetry and so I never felt any weakening of the censorship.

My first collection of poetry went to the publishers in 1971 and appeared in print only in 1977 in a highly abridged form. Meanwhile I prepared a samizdat collection consisting of my poems thrown out from the official collection. I called it Supplement. It was distributed through samizdat channels in several hundred typewritten copies. Later I met quite a few people who knew my name from that Supplement.

Today you can read that collection on my site in the very form it was prepared then: http://www.larisamiller.ru/dopbd.html.

ROC:

The first poems of Guests of Eternity, written in the 1960’s and ’70’s, are overtly political, criticising the Soviet regime, the purges and torture. During these decades you were a teacher of English – did you ever introduce your students to your writing? Did you ever try to have the poems published? If not, was there another purpose in writing them?

LM:

My English-language students never knew I wrote poems at all. I avoided personal relationships at work. As for my attempts to publish these poems I included them in my book and submitted the manuscript to the publishing house. The editor was a nice person, he told me: “Thank you for your trust,” and took out all those poems, which wouldn’t pass the censor anyway. In short, he took out all those poems, which might have been classified as politically subversive, and also the poems containing the word “God”. Those 26 poems made up this collection Supplement widely distributed unofficially.

ROC:

How did your, and your husband’s, political activity shape both your poems and everyday life?

LM:

I have never been engaged in any political or public activities. I think my husband would probably object to the term “political activity” either because he doesn’t consider his human-rights work as political, for him it means helping people. I couldn’t agree with this more.

But of course the fact that our family had been in the epicentre of turbulent events for a long period couldn’t help influencing my poems and my everyday life. I don’t mean just certain unpleasantness. Internally we tried to live as free individuals. For instance, when in 1973 our close friends emigrated to Israel we continued to communicate with them by telephone and by post. Lots of people were afraid to maintain such relationships and crossed out the émigrés from their lives.

ROC:

Could you please elaborate on the 'certain unpleasantness' and the reason why Boris was jailed. Was this because his human rights activities transgressed the political decrees of the time, thereby were deemed a political crime – if so in which way and what was the charge? If this distresses you in any way please ignore it and forgive me.

LM:

Thank God, Boris was never arrested. However, despite his Ph.D. in Physics and Mathematics he had to work as a street cleaner for five years (1982-87). But he stayed in Moscow, with his family. When in December 1986 Gorbachev returned Andrei Sakharov from his exile Sakharov insisted that Boris Altshuler should join his laboratory in the Department of Theoretical Physics at the Physics Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, where he’s been working to this day.

Boris had been actively involved in the human-rights activities in the former USSR. From 1975 he took part in numerous declarations in defense of his arrested comrades, which were broadcast on “enemy” radio stations. He gave much help to Andrei Sakharov and his wife Elena Bonner during Sakharov’s exile in 1980-86. But real trouble began in February 1982 when some KGB officers first came to see my mother at work to warn her about subversive activities of her son-in-law (she was awfully frightened) and in early March I was summoned to the KGB main office where I was seriously threatened. They showed me a whole volume of Boris’s “anti-Soviet” declarations (as they expressed themselves) and said that if he wouldn’t stop his subversive activities he’d be arrested and then he wouldn’t see his children for 10-15 years. They demanded that he stopped communicating with “you know whom” (interestingly, they never once pronounced Sakharov’s name). Two weeks later they summoned Boris himself and repeated their threats and demands.

Boris did not stop helping the repressed human-rights activists, naturally. Our friends abroad came to our rescue then. Our close friends – physicists (Pawel Wasilewski, Dima Roginsgi, Lev Levitin and other) who had emigrated to Israel and to the USA 10 years earlier, managed to organize a broad campaign in our defense: 300 American universities appealed to the USSR authorities “in defense of Boris Altshuler”. There were the appeals from the National Liberal Party of Germany, from Senator Edward Kennedy. Also Chuck Grassley, a Senator from Iowa, sent in 1984 the telegram to the then KGB Chairman Viktor Chebrikov (our friends gave us a copy of it later, when perestroika began and we visited them in the USA) where he expressed concern of persecution of Boris Altshuler and clarified that he is a “Senator from Iowa State which provides the USSR with 10 percent of its feed grains and 6 percent of its soybean annually”. Boris’s Western colleagues – physicists also appealed to the Soviet authorities in his defense. There was much support from all over the world.

As a result we were saved. Authorities just ordered to dismiss Boris from his teaching job, and did not leave any other possibility to work but as a street cleaner, which was not a bad option. The job took about 2 hours per day, no more, with a salary not less than Boris later received in the Academy of Sciences. Our two sons helped him to clean snow after snow storms in winter time. But there were all sorts of “adventures” though, such as the nine-hour search in our apartment in November 1983 (I described it in my book Dim and Distant Days, see the story “My Romance with English”.)

ROC:

To what degree is it possible for poetry to effect political change?

LM:

When in the early 19th century Alexander Pushkin wrote: “We’ll entertain the good people / By strangling at the pillory / The very last tsar / With the last priest’s guts,” this was not the cause of the revolution, which happened 100 years later in 1917, although revolution literally did just that. On the other hand, another great Russian poet, Fyodor Tyutchev said: “We are not destined to foresee what consequences our words may have...”

ROC:

Did the dissolution of the USSR in the ’90’s bring greater freedom to writers? Were there writers/poets who were still willing to be used as a mouthpiece for the State?

LM:

Yes, of course, there was greater freedom after the censorship had been lifted. In 1992, a big collection of my poetry and prose was published. I couldn’t even dream of anything like that in Soviet times. During 1996-98, three more of my books came out from Glas publishers; and in 2000, Glas published my bookDim and Distant Days in English translation, which I mentioned above. In all, 14 books of my poetry and prose came out after the beginning of the perestroika. That would be quite unthinkable in Soviet times.

There are always writers who willingly become a mouthpiece for the State, but in the 1990s we had no State to speak of.

ROC:

What changes has the first decade of the new millennium brought to Russian writers? Is there a greater dialogue with writers/poets from neighbouring countries and/or the West? Is there still the same urgent need for political poetry?

LM:

All the advantages and disadvantages of the 1990s are still there in Russia of the 21st century. Absence of censorship is an advantage, of course, but absence of adequate books’ countrywide distribution system is a disadvantage. There are many book titles published, including very good ones, but people can only buy them in Moscow and St Petersburg. Generally, the population of our huge country, that used to be famous for its readers, is now practically excluded from the cultural process. This is a big problem. People have to make do with what they see on television, and that is a very aggressive anti-culture.

I know little about cultural contacts with other countries, but I’m sure they exist. I know only what happens to my friends, including my friends in England.

Historically, poetry gained political significance when there was a stable totalitarian state, such as the tsarist regime or the USSR. In the new times we live in a state of a painful chaos and poets simply have no idea what they may protest against.

ROC:

How do you see the poet’s position in society and what is the status of poets, both traditionally and in present day Russia?

LM:

About the poet’s position in society the best maxim is by the same Alexander Pushkin: “You are King, so live alone.”

ROC:

Your poetry seems driven by both political and spiritual need. In which way do these forces conflict or complement each other?

LM:

My poetry has never been obeying any political demands, only spiritual. I only write about things that are close to me. And since our politics often interferes with our lives crudely and aggressively this theme has also been of concern to me and caused me to write about it.

ROC:

Could you give an example of an aggressive political act, which enhances, gives insight into, a particular poem, please.

LM:

It happened on 15 September 1976, when we witnessed the arrest and forcible hospitalization into a psychiatric clinic of our friend the composer and singer Peter Starchik. On that day we (me, Boris, his brother, and also the wife and two children of Starchik) went in Boris’s brother’s car to see the paintings of an artist friend. Peter asked us to stop at the police station for a minute because he had received a summons the day before. And there this terrible tragedy took place. Peter’s only guilt was that he gave home concerts, which attracted many people, and some of the songs he performed were not to the authorities’ liking. Those songs were to the words of Marina Tsvetayeva, Osip Mandelstam, poets from Soviet GULAGs (both Stalinist and the later ones.) That was why they decided to put him into a madhouse. “Punitive psychiatry” was widely used at that time. All those witnessing his arrest knew that he would never be released from the madhouse. It was really frightening. When the ambulance started from the police station Peter’s wife tried to run after it. How she shouted! I can hear it even now, 34 years after the event. That night I wrote the following poem: “Look, my darling, / the cradle is hanging over an abyss” (page 47 in Guests of Eternity.)

However, Peter Starchik had been rescued that time after all. Boris wrote an appeal to the French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing. It was signed by many friends. The fact that in the USSR a person had been arrested “for singing songs in his own home” aroused a storm of protest in the West and Peter was released two months later. The “treatment” he had been subjected to was a torture in fact. I describe the incident in more detail in my book Dim and Distant Days.

Another example which you ask about is the poem “I have good news... we’ve still survived and are in place” (page 67 in Guests of Eternity). It was written a few days after Sakharov had been arrested in a Moscow street and sent for an exile to Gorky, it happened on 22 January 1980. Boris was very close to him and I really did not know what may happen the next day.

ROC:

The transcendental infuses your poems. Does this stem from your Jewish heritage or does it go beyond the conventions of established religion?

LM:

Yes, it goes beyond the conventions of established religion. I don’t share the beliefs of any confession.

ROC:

Could you elaborate on the ‘transcendental’ element, please. What do you mean by it and perhaps give examples from your poems.

LM:

In the first place, like probably many poets, I’m often visited by an acute sensation that it’s not me who writes a poem but someone from high above dictates it to me and I’m simply writing it down. So this sensation of the transcendental is probably part of the creative process. I often feel as if I “speak to Heavens” and it is my best interlocutor. I have many such poems, including in my book Guests of Eternity. See, for example, the pages: 43 (It seemed all was marked), 45 (Our life is sewn), 47 (And instead of grace), 69 (To go out once from fate), 71 (Another flight, more steps), 123 (What is there overhead), 127 (I’m on about my own stuff).

ROC:

Your poetry is noted for its integrity, which perhaps suggests that the spiritual journey or political ideal is the dominant factor rather than one which is language driven. Would you care to comment on this, please?

LM:

“Spiritual journey” is a good description of my poetry. Thank you for it.

ROC:

What does the phrase ‘poetry without words’ mean to you?

LM:

This phrase is certainly a metaphor. Its meaning becomes clear when you compare concrete poems and concrete authors. I’ve written an essay on this subject: “If only I could do without words...” Some authors are very eloquent while others use simple language allowing for more air in their verse. Such “wordless” poems as it were are more reminiscent of an air current than a stream of words.

ROC:

How far do you believe ‘The word is conditional, like a pose or gesture:’? (A word is a tear. 1985). Does this indicate mistrust of the word as an instrument of communication?

LM:

The word is certainly conditional. The person who has learnt a dictionary by heart will still be unable to communicate adequately with the help of mechanically memorized words. The word becomes an instrument of communication only when it creates multiple associations, that is, when our entire consciousness, our subconscious and our imagination are participating in the process.

ROC:

In your essay “Homo Ludens” (Man at Play) 1996 you wrote ‘hardest by far is to maintain order within that space, which is entrusted to us...’. Would you elaborate on this, please?

LM:

I believe that man’s inner problems, his personality problems are the most important ones. That is why people say: “You can be free in prison and a slave in freedom.” It is said in the Bible: “God’s kingdom is within us.”

ROC:

Is being a poet a gift or a burden – or both?

LM:

Both.

ROC:

Could you elaborate on which way being a poet is a) a gift b) a burden.

LM:

Beginning with the age of 16 and up to 23, when I’d already graduated from the Foreign Languages Institute, took on a teaching job, and married Boris (we’ve been together for 47 years now) I was in constant torment. I saw no purpose in life. My torment was over when I started writing poetry. In this sense poetry is certainly a gift, at least for me.

But you can’t write poetry all the time. Moreover, this euphoria from a successfully composed poem soon passes: you experience this joy for maybe one day at the most. Then come gloomy, depressing thoughts that it may be my last poem and I wouldn’t be able to write another. And then again poems come from God knows where followed by this terrible depression again. That’s a real drudgery: I can’t help writing but the burden is heavy.

ROC:

Which poets have influenced you and why?

LM:

At different periods in my life I was infatuated with different poets. I love many of them to this day. But I can’t say any of them influenced my own poetry.

ROC:

Is there a strong tradition of women poets in Russia or has the poetry scene been traditionally patriarchal? Has the fact of being a woman ever hampered your development as a poet?

LM:

Your question is related to the 19th century and the earlier times, when the woman was believed to be a second-rate creature. I have never felt any gender discrimination myself.

ROC:

How do you see, and how would you like to see, the poetry scene developing in Russia in the next decade?

LM:

I’m sure that in poetry, the same as in art in general, there are no such notions as progress and development. And you can’t possibly apply them to such short stretches of time as a decade.

ROC:

Are there any other topics you would like to comment on?

LM:

I’m still under a strong impression from my recent visit to England in the end of 2008. And I’m particularly shaken that my poems, which are mostly called ‘wordless” (we’ve discussed this above), now in the English translation by Richard McKane, made with words, inspired such a strong emotional reaction in my English speaking listeners and readers. I regard this as an inexplicable wonder. My husband wrote about it under the Title “Enigma of translation: question without answer”. It is placed on my web-site: http://www.larisamiller.ru/pres_g_o_e_e.html.

ROC:

Thank you.

February 2009

Ruth O'Callaghan, a winner in International Poetry competitions, hosts three poetry venues in London and is frequently invited to read both in the U.K. and abroad. Her work, which is published in many anthologies and magazines, has been translated into Italian and Romanian. A competition adjudicator, interviewer and reviewer, she has also been a reader/compere at Richmond's Book Now Literary Festival. Her collection Where Acid Has Etched (Bluechrome Publ.) was published in June 2007.

This interview in Russian (translated by Boris Altshuler; the translation was made from the extended version of the interview made in 2013 and presented at meetings with readers in Great Britain).

|