|

'Everyone with a three for the term fetch your satchels and get in line,' said Lydia Sergeyevna. 'Now quick march after me to the cloakroom. You're going home. The others go quietly into the hall and take your places. You're going to watch a puppet show – Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.'

We girls from 2-B with threes (there were no coeducational schools in those days) shuffled out behind our teacher, heads hung low. 1 tried not to look at the makeshift stage set up in the hall, but couldn't stop myself and through my tears I caught a glimpse of green spangled curtains and rows of benches where the girls with fours and fives were hopping up and down excitedly. My satchel felt like lead: inside was an end-of-term report with a three for maths. My only three for the term, and it had done me out of the puppet show, a happy homecoming and carefree winter holidays. There was just one week to go before the New Year, 1949.

I went outside and set off home without even saying goodbye to anyone. In our yard I met Mother who had left work early in honour of the school holidays. Seeing my woebegone expression, she began to interrogate me. I took out my report, showed her the three and told her everything. Next day Mother came home from work and put her bag down on the table. 'Guess what's in here,' she said. The bag was literally crammed with theatre and concert tickets, lots of them. The New Year celebrations were about to begin. Everyone got caught up in it: Granny, Grandfather, Mother, even Mother's friends. I went to the operetta with Mother, to the opera with Grandfather, and to plays and the concerts with Granny.

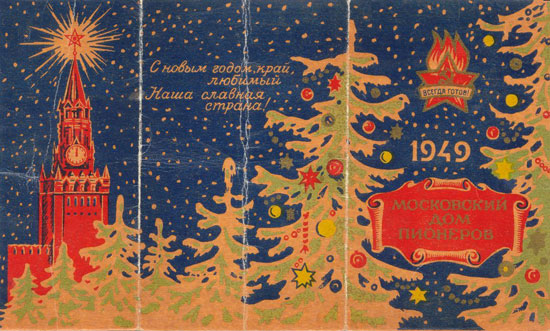

'Happy New Year, dear country, glorious land of ours!' sang the golden letters on the ticket for a children's concert at the Young Pioneers Palace. The ticket showed 1949, the New Year, as a young man in a sheepskin jacket and fur cap with earflaps skiing towards Grandfather Frost who was carrying a sack out of which stuck Gaidar's book Timur and His Team. It was a splendid ticket indeed.

'First look at me / in the electric light, / Then turn it right off / And my tree will shine bright.' This little ditty was printed on the back of a ticket for the Columns Concert Hall. On the front was a rosy-cheeked, bright-eyed Young Pioneer in a white shirt and red tie holding a crimson star. The red of his banner, star and cheeks were fiery and festive.

The holiday began in the morning. I went into the yard with my ticket to boast to the other children. They had brought theirs too and we argued about which was best. One day I went out with my finest ticket of all, to a concert at the Central Club of Artists. It was a trick ticket. When you opened it, out popped a big bushy fir tree decorated with streamers, tiny animals and Grandfather Frost in a sledge with the Snow Maiden. Presiding over all this in the star-spangled heavens was Stalin's face. The ticket was passed from hand to hand. 'Let's have a look', said the boy next door, Yurka, who I'd had rather a soft spot for since he'd come back, from the Suvorov military school for the holidays. I handed him the ticket not suspecting a trick.

The other boys crowded round him, inspecting it closely and whispering. 'Come here,' Yurka called, standing by our entrance to the stairway. 'Take a lick of that door handle'. 'Whatever for?' I said in surprise. 'You'll soon find out.' I hesitated. 'Take a lick,' Yurka wheedled. 'It's nice and sweet. Everyone else has had a go.' I was eager to do anything for him, so I licked the icy-cold metal door handle. In that severe frost my tongue stuck to the metal at once, Yurka and the boys ran off, laughing. I managed to pull my tongue away, leaving flecks of blood on the handle, then went home, forgetting all about the ticket and the concert. When evening came and Granny told me to hurry up, I realized that we weren't going anywhere, Yurka had gone off with the ticket. I told Granny I had lost it, then went to bed, pulled the blanket over my head and burst into tears. I cried for ages, wiping my tears on the sheet, until at last I fell asleep.

The next day there was another concert. And not just an ordinary one, but at the Trade Union House. In those days grownups were allowed to accompany the children. It was so exciting to walk into the huge dark hall holding Granny's hand with music playing quietly and snowflakes drifting down. I took my seat and looked around. As if entranced by the magic snowstorm, the audience's chatter was hushed. Suddenly up went the lights and out boomed the master of ceremonies' voice – the show had begun.

My favourite number was the dance of the butterfly. A little ballerina dressed in something white and frilly fluttered onto the stage. She spun round in circles as she danced. One circle and her dress turned blue, another made it rainbow coloured, then chocolate brown, then yellow. The rays of the floodlight followed the little butterfly wherever she went, changing the colour of her wings. Each transformation was accompanied by appreciative 'oohs' and 'aahs'. Then the light went out and there she was again in her white costume.

There was one more number I always looked forward to: the two Nanais' wrestling match. Two tiny figures grappled with each other doing their darndest to pin the other fellow's shoulders on the ground. They rolled round the stage, falling down, bouncing up again, crouching in corners and whizzing over the floor. The audience roared: the children clapped like mad, jumping up and down and yelling advice. Suddenly one of the Nanais flew up into the air, felt boots and fur coat flashing past for the last time, and disappeared. There in place of the two stood a dishevelled, sweating young man, with two pairs of felt boots on his arms and legs. The audience was quiet for a moment, then burst into thunderous applause. No matter how often this number was shown, the effect was always the same: the roaring audience, the sudden hush, then the burst of applause.

After the concert everyone rushed over to the huge Christmas Tree to watch the lighting-up ceremony. 'One, two, three – light up, fir tree!' boomed Grandfather Frost, with a blow of his staff, and the tree lit up. This was greeted by the usual chorus of 'hoorays' and then at last Grandfather Frost asked: 'Who's going to recite us a poem?' Me, of course. I knew so many poems I could go on reciting till the cows came home. So out I went and began: 'Little Moscow girls have two pigtails, little Uzbek girls have twenty-two...' or 'We children live in a happy land and a happier land there cannot be...' or 'At this late hour Stalin is thinking of us all...'

Then Grandfather Frost took me by the hand and gave me a present from the tree. After that there was dancing. I was always a little snowflake in a white skirt and white crown.

At one such party a prince in tights and a golden jacket came up and asked me to dance. He had a shining crown on his head and stayed with me all evening. We went to get presents together, and when finally in the cloakroom my paper packet burst and the sweets and gingerbread fell out and the tangerines went rolling all over the floor, my prince rushed to pick them up. I felt like Cinderella at the ball and was in such a hurry that I couldn't get my arm into the sleeve of my coat. Quick, quick. He's waiting. Now I'm ready. But where was he? Looking round, I saw a tall thin girl standing next to me. Her face seemed familiar. 'I'm Tanya,' she said. ' That's your prince,' laughed a tall young woman, very like Tanya, Tanya's mother. We walked towards the exit. Granny chatted to Tanya's mother, and Tanya tried to talk to me, but I hardly heard what she was saying and made some vague replies. We parted company at the bus stop.

Very often the winter holidays dragged on due to illness. At the end of the holidays I usually got a sore throat or earache, or swollen glands and a high temperature, and gladly let myself be tucked up in bed. One day I found myself standing on the table, pointing at the wall and whispering: 'A red ribbon, there's a red ribbon on the wall'. Mother and Granny exchanged horrified glances. 'Agree with her,' Granny whispered. 'When a child is delirious, you must agree with it.' What happened after that, I don't remember. Later I learnt that I had scarlet fever.

Being ill as a child was sheer bliss. It meant fever and feeling a bit dizzy. An anxious and caring mother who didn't go to work and made you jelly and put mustard poultices on your back. Being ill meant that they read to you and when your temperature went down they'd let you have books, pencils and drawing paper in bed. Being ill meant drinking a nice sweet cough mixture prescribed by the district doctor Bukharin, the excellent children's doctor, a kindly and perpetually tired elderly woman, who disappeared suddenly and completely in the early fifties. I later learned that she had been arrested because of her unfortunate surname, although she had nothing whatever to do with that 'enemy of the people', the ex-leader Nikolai Bukharin.

Trying to recall all the holiday entertainment made my head woozy. My favourite plays were The Twelve Months and The Blue Bird. I had seen them a hundred times and would gladly go again. What I liked best in The Blue Bird was the Other Kingdom and Running Nose played by a young woman with a big red nose who ran round the stage sneezing all the time. And in The Twelve Months I liked the storyteller in striped trousers. He came out before each act and jigged up and down in a funny way, chanting something like 'bim-bam-boogy, boogy-baziloogy'. I also remember a play called Snowflake that I saw with Granny at the Children's Theatre. Snowflake was a poor little black boy, oppressed and downtrodden. He was tormented and persecuted by the white Yankees in hateful America. How I wished I could save that little boy, spirit him away to Moscow, give him a nice warm home and comfort him!

What else did I see? I tried to reconstruct everything right from the beginning and suddenly saw clearly the school hall, the green spangled curtains and the large notice in flowery handwriting: Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, the most interesting, desirable and inaccessible show of all, the forbidden fruit of my childhood.

|